One of the things I always like to do is a sort of after-action review of any disasters that come our way.

We can learn a lot by looking back at what has happened and how people reacted to it, even if we weren’t personally affected by the disaster. Those lessons maybe what we need to learn to survive the next upcoming catastrophe.

I’ve already discussed the cascading effects of the February 2021 freeze and how a simple cold front should have been a simple cold front, albeit a rather severe one, turned into a dangerous situation, as one system failed after another. After having experienced that, it seems to be what we can expect to find happening in any future disaster.

The infrastructure that we have created in modern society is incredibly complex. But as we have seen, each piece of it is dependent upon others. So what starts to affect one part of our lives can quickly grow into something that affects everything we depend on.

We talk about this when we talk about the effects of an EMP or CME. But we don’t necessarily apply it to other potential disasters. It’s commonly believed that those grid-down events will cause significant disruption to our lives, leading to many people dying. But we don’t expect something relatively minor to have the same effect. Yet if that freeze was any example, we’ve reached the point where things that seem to be relatively minor can end up having a rather significant impact.

We Can’t Count on Our Plans

One of the first things in the Texas freeze was freezing rain, impacting even before the power went out. Texas is a state where “freezing” usually means that it’s under 60°F, not enough to freeze much of anything. Yet this freezing rain turned the streets to ice, causing a nearly 100 car pileup in Fort Worth.

Freezing rain may not seem like much of a problem, but it can immediately invalidate our plans to get home, as well as any plans to bug out and ride out the disaster in a remote survival retreat somewhere. I have yet to see anyone who has a bug-out vehicle that’s designed to be able to drive on black ice. Anyone whose primary survival plan involved bugging out suddenly found their plans thwarted before they could even start to put them into effect.

Did those people have a backup plan? Were they prepared to bug in, as well as bug-out? If they lost power while stuck in their homes, were they prepared? Or were all their plans based upon being able to bug out and get to their survival retreat?

I don’t care what your plans are; there is always a chance that you won’t implement them. There are just too many variables involved in any survival scenario for us to be sure that we know what will happen ahead of time. That leaves us making some educated guesses along the way, any one of which can be fatally flawed. Then what?

That’s why any plan we come up with needs alternatives, not only an option for the overall plan but options for every portion of our overall plan. There’s no way we can know beforehand what is going to fail and what is not. We’ll find that out when it’s too late to do any more planning. While improvising on the fly is a useful ability, it’s not something we want to count on.

The word is redundancy, and while it is something we talk about when it comes to the gear in our bug-out bags, we are great at talking about it. But when it comes to the rest of our preps, it can easily get forgotten.

Stay Flexible

Plans are exciting things. We’ve got to have them, but at the same time, we can’t count on them. We have to be ready to abandon or modify our plans immediately, even while trying to survive the situation.

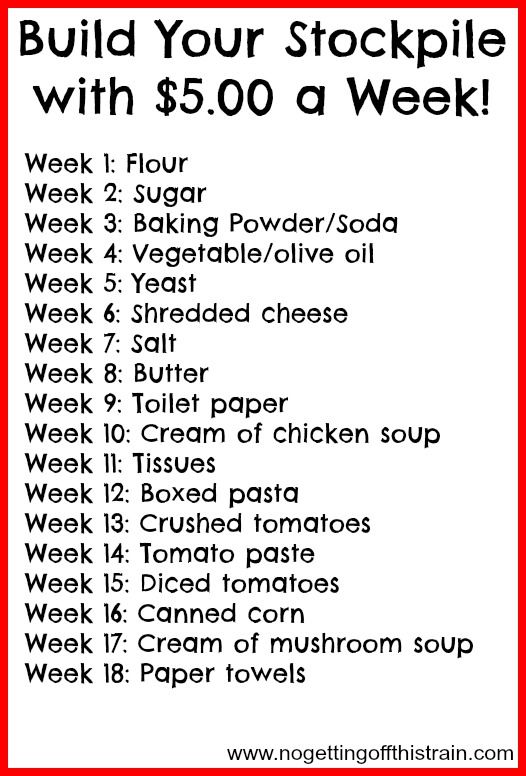

One of the reasons that we make plans is to give us a framework for preparation. Even if we don’t follow our plans exactly, most of what we do to prepare for implementing that plan will be useful. A stockpile of food and supplies, the ability to purify water, and start a fire are pretty much universally useful, regardless of what happens.

The other big reason why we plan is that it is tough to think clearly during a crisis. The “fight or flight reflex” injects massive amounts of adrenalin into our systems so that we can run or fight. But that same adrenalin makes it harder for us to think, as well as lowering our dexterity. That makes it harder for us to do a wide range of tasks, such as shooting a gun and starting a fire. At the same time, we struggle to reason through the situation.

Nevertheless, that’s precisely what we need to do, apply reason to the situation, thinking things through, and deciding what the best course of action is in that exact situation. That might mean staying home and bugging in because of the black ice, even if we don’t have power and water.

So, we all need to be ready both to bug out and to bug in. While most survival writers today recommend bugging in as our first option, the people of Paradise, California, were forced to bug out when their town burnt to the ground. I sure hope they all had their bug-out plans in order.

Have Multiple Bug Out Plans

It’s hard to develop the perfect bug-out plan when we don’t know when we’ll be bugging out or why we will be doing so. That puts us in the position of creating a bug-out plan that is based upon a series of assumptions. While that is necessary, it’s also dangerous.

If our central premise for bugging out is to avoid social unrest, how do we know that the same turmoil will let us bug out? How do we know we’re going to be able to get to our survival retreat? How do we know that our retreat won’t already be occupied when we get there?

The only reasonable solution is also one that’s hard and potentially expensive to do; create multiple bug-out plans. That way, when the time comes to bug out, we can decide which one to put into effect, based upon what dangers we’re trying to get away from. Should our first option not work out as we hoped, we’ve got something else we can do as an alternative.

I had this in operation where I used to live. Since I was right on the border with Mexico, my alternate bug-out plan was to jump across the border and head south. While that wasn’t my main plan, I have enough friends in Mexico that I would have my choice of places to go. While that plan would not be as convenient now, it’s still an option for me since I live farther from the border.

Have More than One Source

We stockpile to have equipment and supplies which we can use to get us through a disaster and its aftermath. But what do we do if we’re faced with a long-term survival situation? How do we continue to survive, past where our stockpile will take us?

That is why many of us focus on self-sufficiency rather than just focusing on surviving as long as our supplies last. The more self-sufficient we can become, the greater our chances. But some things, such as firewood, go beyond what we can grow ourselves to something that we’re going to have to procure elsewhere, whether from nature or other sources, perhaps warehouses.

Take firewood, for example. Few preppers have enough firewood to make it through one winter, let alone more. Unless someone regularly heats with wood, they are unlikely to realize just how much wood is needed. But even if they do, it’s doubtful they’ll have more than only one winter.

Okay, so what do we do when whatever quantity of wood we have runs out? Where will we get more from? If you’re thinking of the trees around the neighborhood and in some local park, think again. The chances are that people who are less prepared than you will cut that down long before you need it. That leaves you with needing to range farther afield in search of firewood, probably outside of town. Can you do that? How will you haul the wood back home?

I don’t care what it is or how unorthodox you’ve got to be to come up with it. You need more than one source for everything you’re going to need. If that means taking abandoned buildings apart to get wood, then make a plan for it. If it means eating neighborhood cats and dogs, then figure out how you will do it without the neighbors knowing what you’re doing.

Backup Methods for Key Survival Needs

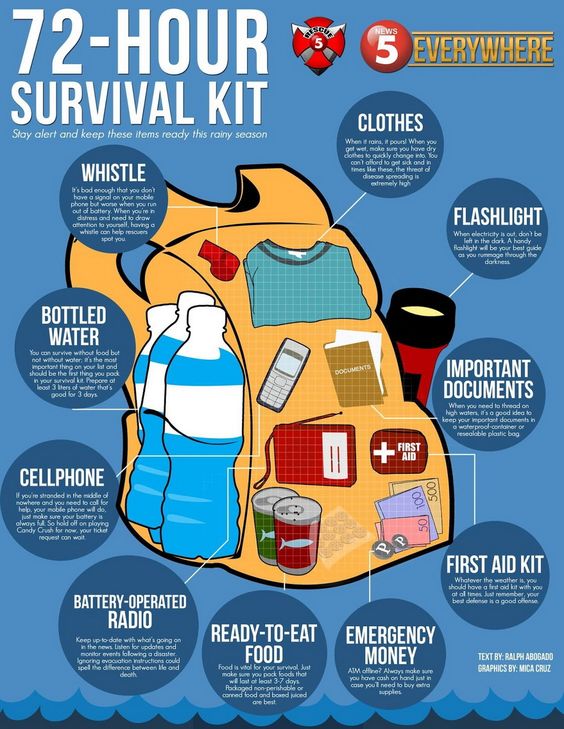

Don’t just have backup sources for the things you need; make sure you have at least one backup method (preferably more) for any critical survival task you’ve got to do. Just like having more than one place to get firewood from, you should have more than one way to cut that wood. Equipment breaks and wears out, so you’ve got to have a way to keep going when that happens.

I see way too many preppers who depend on just one way of doing something critical, such as gathering water and purifying it. They’re planning to get water from the canal nearby and filter it through a water filter they bought. Okay, what if some gang takes over that canal and won’t share the water? What if the water plugs up the filters faster than they expected? What’s the alternate?

This basic concept is the reason behind survival instructors teaching multiple different ways of starting a fire. You’re going to need a fire to survive, no matter what. So you need ways that you can fall back on when your disposable lighter runs out of fluid, and you lose your Ferro rod.

Make Sure You Have Quality Gear

I’m a bit of a toll collector. A lot of that is because I’m a consummate do-it-yourself. I’ve accumulated quite a workshop full of tools through the years, and my collection is still growing. That’s not just because I can always find more tools that I want, but also because I keep working on new things, which require tools I don’t have.

But there’s something else I’ve noticed through the years. That is, many of the lower-cost tools I bought when I was younger didn’t last. In many cases, I’ve had to replace those tools. Some of the old ones are still in my workshop, while others found their way to the trash.

So why did I have to replace those tools? Because they couldn’t keep doing the job they were made to do. That’s bad enough in my home workshop, where I can run to the local home improvement center for a replacement; it could turn into a life or death situation if I were out in the woods or a grid-down survival situation.

I don’t care if you’re buying a knife, saw, or drill; quality generally means higher-cost materials, which are more durable and resistant to breakage. That’s really what you’re paying for when you spend more money on tools. When it comes to survival, that higher quality material could very well be what keeps you alive. Trusting in a low-grade knife that ends up breaking could be a cheap way to lose your life.

Always Have a Spare

If you already have a bunch of cheap survival gear, don’t despair. Keep those things around as spares. While it may not last as well as what you replace it with, having it is better than not having it. Maybe it won’t last long, but hopefully, it will last long enough for you to fix your original or make something else.

I tend to collect survival gear, mostly because of what I do. Companies send me things to try out, and I buy others due to my curiosity. Then, I believe I’m replacing what I was already using with something that I think will work better. That doesn’t mean that I throw away the old gear, merely that it is moved from my main survival kit or bug-out bag to a less critical role.

Take shovels, for example. Somehow, I’ve managed to gather several survival or camping shovels through the years. The best one has become part of my bug-out bag. I’ve got another good one in the trunk of my car, alongside my EDC/get-home bag. Still, another is in my wife’s car, with the emergency kit I keep there. And I’m sure I’ve got one or two in the garage. Should a disaster strike and I bug in, I’ve got them all to use. But even if I bug out, I’ll probably have at least two.

Along with having a spare, be ready to repair what you’ve got. Even if you’re not the world’s best handyman, make sure you’ve got some basic tools, hardware, wire, duct tape, and superglue. A jury rig fix is just as good as doing it the right way if it works. So be ready to make that gear into its spare by repairing it when and if it breaks.